15. September 2025

Behind the Lens

ASK ME – or What Would Jakob Bronner Say?

by Hannah Landsmann

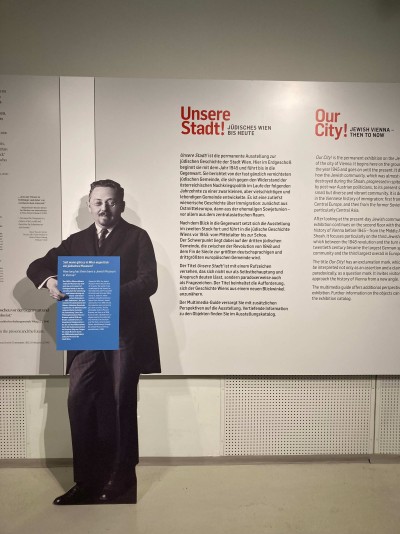

Portrait of Museum Curator Jakob Bronner, Vienna, c. 1930, JMW, inv. no. 1737

Of the 130 years that the Jewish Museum Vienna celebrates this year, Curator Jakob Bronner was part of the story for twenty-two years. It is his part of the story that we will now share within the permanent exhibition of the Jewish Museum at Dorotheergasse 11. The first Jewish Museum was founded in 1893 and officially opened its doors two years later. The Jewish Museum Vienna today is its successor institution, having been reestablished in 1988 after the Shoah.

We honor the memory of Jakob Bronner with an intervention in the permanent exhibition Our City! Jewish Vienna – Then to Now. Jakob Bronner was born in 1885 in the Habsburg crown land of Silesia and taught religion at the Gymnasium in Wasagasse in Vienna. In 1916, Jakob succeeded his brother Moritz/Maurice Bronner as the curator of the Jewish Museum Vienna. At eight selected locations throughout the exhibition, visitors can now meet Jakob Bronner and get to know the extensive history of Viennese and Austrian Jewish history through his unique perspective. Each of the eight stations poses a question, which is then followed by a short text that partially quotes Bronner’s own publications. Where was the first Jewish Museum located?

© JMW

View of Jakob Bronner at the beginning of the permanent exhibition

Why was the “Gute Stube” created? Who were the Jewish heroes of the 1848 revolution? Did the first Jewish Museum collect objects related to Jewish women’s history? What happened in 1938 to the museum and the objects stored and displayed at Malzgasse 16 in Vienna’s second district?

© JMW

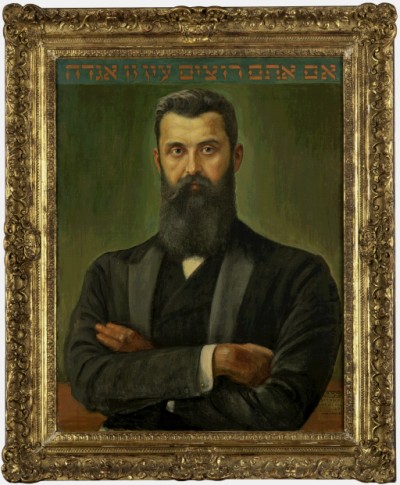

Wilhelm Wachtel, Portrait of Theodor Herzl, oil on canvas, Vienna, 1930, JMW inv. No. 8179; Photo: David Peters, JMW

If only Jakob Bronner could truly answer these questions himself - or at least have left behind a diary from which we could glean details of his life and work at the museum. Sadly, that is not the case, so we can focus only on the facts we can draw from existing sources. For example, the bullet that struck and killed revolutionary Carl Heinrich Spitzer in 1848 was once part of the collections of the first Jewish Museum. This information comes from the inventory book of our predecessor institution. The bullet is no longer in the collection. We cannot determine what happened to it - whether someone pocketed it or it simply was lost. “Nothing gets lost in museums,” they say...

In 1938, Jakob Bronner had to leave “his” city and fled to Palestine. He took with him a copy of a list he had been forced to prepare for the Gestapo, which shut down the Jewish Museum in May 1938. This list recorded the museum’s inventory at the time. The list had to be compiled in haste. In 1955, Bronner - who died in1958 - sent the copy to the Jewish Community Organization of Vienna (IKG). The objects stolen and confiscated in 1938 ended up in other Viennese museums and were used in an antisemitic exhibition at the Natural History Museum in Vienna, which ran from 1939 to 1942. After World War II, the list helped clarify the provenance of the objects that were eventually restituted.

In 1992, the Jewish Community Organization of Vienna gave a large collection of objects from its holdings to the Jewish Museum Vienna, among them Torah ornamentation salvaged from the destroyed synagogues and prayer houses in the November pogroms of 1938. These permanent loans serve as a reminder of the size of the Jewish communities in Vienna and Austria, their destruction, and the first Jewish Museum and its closure. In this sense, the large display case on the third floor is also a memorial.

The permanent exhibition Our City! draws on this collection and allows the past and the present to interact with one another, ideally with the future as well in the hope of making it a little better.

© JMW

This soup cup was on display in the “Gute Stube” installation of the first Jewish Museum. The Nazis confiscated this object in 1938 and gave it to the Ethnological Museum in 1939. After 1945, the soup cup was restituted to the Jewish Community Organization of Vienna (IKG).

© JMW

Picture postcard of the “Gute Stube” at the first Jewish Museum, Vienna, um 1900, JMW inv. no. 917

During your visit to the Jewish Museum, take the opportunity to engage with the permanent exhibition - where Jakob Bronner might be astonished, enthusiastic, or reflective about what he sees and reads. The famous “Gute Stube,” once a true museum highlight, was shown in 1911 at the Hygiene Museum in Dresden and even featured on a postcard as a merchandise item.

© JMW

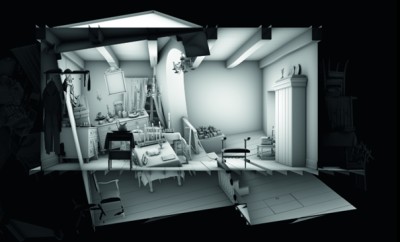

Detail from Maya Zack’s installation The Shabbat Room, Israel, 2013, JMW, inv. no. 21069. Purchased by the FRIENDS of the Jewish Museum Vienna and Peter and Carry Frey, 2013; Photo: Klaus Pichler, © JMW 2013

In 2013, Israeli artist Maya Zack reinterpreted it in a modern way. Her digital reconstruction, located on the second floor of the museum, explores the essence of this special room. What would Jakob Bronner have said about it? Or Samuel Weissenberg, who collected and researched for the first Jewish Museum and described the room as a place where “a Jewish heart could rest.” Would Jakob Bronner think one could rest here today? We cannot say for sure, but we can reflect on whether a museum can be a place of rest.

© JMW

View of Jakob Bronner in front of Maya Zack's installation in the permanent exhibition