18. September 2023

Expo Window

Expo Window: “Making Room for God.” The Day of Atonement

by Gabriele Kohlbauer-Fritz

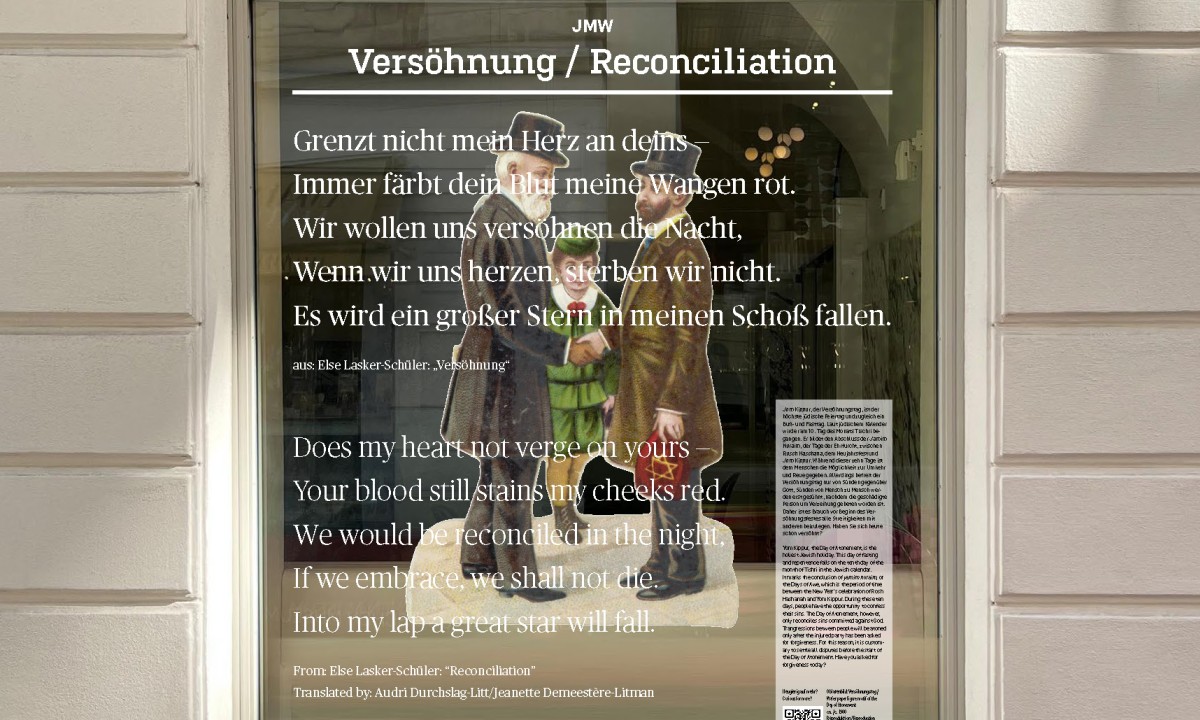

“The world of the Jew will eternally include this day, and it will, at some time, stand before God as a creation in His own image. Hatred and strife are sung to sleep smiling, like tired, stubborn children,” said the poet Else Lasker-Schüler in her essay “The Day of Atonement.”

The Day of Atonement, also known as Yom Kippur, is the highlight of the Jewish holidays at the beginning of the Jewish year. Before the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, it was the only day on which the High Priest entered the Holy of Holies and pronounced the name of God. He did this three times during the confession of guilt, once for himself, once for his house and the priests, and once for all Israel. One of the special atonement rituals of Yom Kippur was casting lots for two goats. One goat was presented in the temple as a propitiatory sacrifice and the second was symbolically sent into the desert laden with the sins of the people of Israel. After the destruction of the Second Temple, sacrificial rituals were replaced by liturgical rituals. Since then, the Day of Atonement has been spent in prayer and fasting in all Jewish communities around the world. Pious Jewish women and men often dress in white as a sign of purity and awareness of their own mortality, and they do not wear leather shoes to commemorate the suffering of animals, who are also God’s creatures. The Day of Atonement is the ceremonial conclusion of the Jamim Noraim, the “Days of Awe,” between Rosh Hashanah (New Year) and Yom Kippur.

“On Rosh Hashanah it is inscribed, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed – how many shall pass away and how many shall be born, who shall live and who shall die, who in good time, and who by an untimely death...”

is written in the famous medieval liturgical poem “Unetane Tokef,” whose author is considered to be Rabbi Amnon from Mainz and which also inspired Leonard Cohen to write his song “Who By Fire.” According to a Talmudic legend (Talmud Yoma 8:9), three books are opened on New Year’s Day: the “Book of Life” for the righteous, the “Book of Death” for the wicked, and a book for those whose judgment has not yet been determined. The final judgment will be suspended until the Day of Atonement. Through “repentance, prayer, and charity” during Jamim Noraim people have the opportunity to return to the right path and influence their fate in order to be recorded in the “Book of Life.” Since most people are neither absolutely good nor absolutely evil, but rather lie in the gray area in between, everyone is asked to repent their sins and ask God for forgiveness. However, the Day of Atonement only frees one from sins against God; sins from person to person are only atoned for after the wronged person has been asked for forgiveness. Therefore, before the beginning of the atonement festival it is customary to settle all disputes with others and, if possible, to make amends for injustices that have been done to others.

The universal claim of the Day of Atonement, which embraces all people in divine grace, is expressed in the haftarah of the morning prayer, where a chapter from the Book of Isaiah explaining the deeper meaning of fasting is read. And for Else Lasker-Schüler, the Day of Atonement is also associated with messianic hope: “He will come back at the end of the world, the embodied Day of Atonement, the Messiah. Because only the reconciliation of all people is able to uplift and redeem (...) It is not the fasting of the stomach if the soul, stripped of all baubles, does not shimmer: ‘Making room for God.’ The fasting of the soul is what matters, because in these grand hours it shall fill itself with the inexhaustible, jubilant love of the Day of Atonement.”

The Day of Atonement, also known as Yom Kippur, is the highlight of the Jewish holidays at the beginning of the Jewish year. Before the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, it was the only day on which the High Priest entered the Holy of Holies and pronounced the name of God. He did this three times during the confession of guilt, once for himself, once for his house and the priests, and once for all Israel. One of the special atonement rituals of Yom Kippur was casting lots for two goats. One goat was presented in the temple as a propitiatory sacrifice and the second was symbolically sent into the desert laden with the sins of the people of Israel. After the destruction of the Second Temple, sacrificial rituals were replaced by liturgical rituals. Since then, the Day of Atonement has been spent in prayer and fasting in all Jewish communities around the world. Pious Jewish women and men often dress in white as a sign of purity and awareness of their own mortality, and they do not wear leather shoes to commemorate the suffering of animals, who are also God’s creatures. The Day of Atonement is the ceremonial conclusion of the Jamim Noraim, the “Days of Awe,” between Rosh Hashanah (New Year) and Yom Kippur.

“On Rosh Hashanah it is inscribed, and on Yom Kippur it is sealed – how many shall pass away and how many shall be born, who shall live and who shall die, who in good time, and who by an untimely death...”

is written in the famous medieval liturgical poem “Unetane Tokef,” whose author is considered to be Rabbi Amnon from Mainz and which also inspired Leonard Cohen to write his song “Who By Fire.” According to a Talmudic legend (Talmud Yoma 8:9), three books are opened on New Year’s Day: the “Book of Life” for the righteous, the “Book of Death” for the wicked, and a book for those whose judgment has not yet been determined. The final judgment will be suspended until the Day of Atonement. Through “repentance, prayer, and charity” during Jamim Noraim people have the opportunity to return to the right path and influence their fate in order to be recorded in the “Book of Life.” Since most people are neither absolutely good nor absolutely evil, but rather lie in the gray area in between, everyone is asked to repent their sins and ask God for forgiveness. However, the Day of Atonement only frees one from sins against God; sins from person to person are only atoned for after the wronged person has been asked for forgiveness. Therefore, before the beginning of the atonement festival it is customary to settle all disputes with others and, if possible, to make amends for injustices that have been done to others.

The universal claim of the Day of Atonement, which embraces all people in divine grace, is expressed in the haftarah of the morning prayer, where a chapter from the Book of Isaiah explaining the deeper meaning of fasting is read. And for Else Lasker-Schüler, the Day of Atonement is also associated with messianic hope: “He will come back at the end of the world, the embodied Day of Atonement, the Messiah. Because only the reconciliation of all people is able to uplift and redeem (...) It is not the fasting of the stomach if the soul, stripped of all baubles, does not shimmer: ‘Making room for God.’ The fasting of the soul is what matters, because in these grand hours it shall fill itself with the inexhaustible, jubilant love of the Day of Atonement.”