As a JMW Intern, I have spent the past several months researching the Danube Regulation (1871-1875) and its impact on the Jewish residents of Leopoldstadt. My project is linked to my American Fulbright grant that allows me to live, work, and research in Vienna. I chose Leopoldstadt for my research because it is the epicenter of Jewish life in Vienna. Due to the large percentage of Jewish-Austrians living here, it earned its nickname Mazzes-Insel, referring to the unleavened bread Matzah and its location between the Danube Canal and River. When I approached my research questions from the US, I expected to find clear divisions between Jews and non-Jews in Vienna's 19th-century urban planning, something that would be reflected in the Danube’s many intersections with Viennese life. Instead, I found that Jews who worked on the regulation did not see their participation as linked to their Jewishness or Jewish life on the Mazzes-Insel, but rather that they shared a modernizing vision for the city with their non-Jewish neighbors and colleagues.

The Danube Regulation was crucial for Vienna’s growth. It controlled flooding, stabilized the Danube’s course, and protected the city. This enabled safer living conditions, expanded urban development, boosted trade, and laid foundations for Vienna’s transformation into a modern European capital. At the time, civil engineers and local politicians recognized the significant impact that this massive effort would have on the second district.

In a letter to Lower Austria’s legislature requesting approval for the project, the municipal council of Leopoldstadt underscored the need to regulate the Danube. “In addition to its general importance for the national economy and trade, the regulation of the Danube next to Vienna is of particular importance for the capital, and especially for its second district, for which it is a real matter of survival.”

(Ley, Konrad. Donau Regulierung, 4. October 1865, Wien Bibliothek im Rathaus, Vienna, p.3)

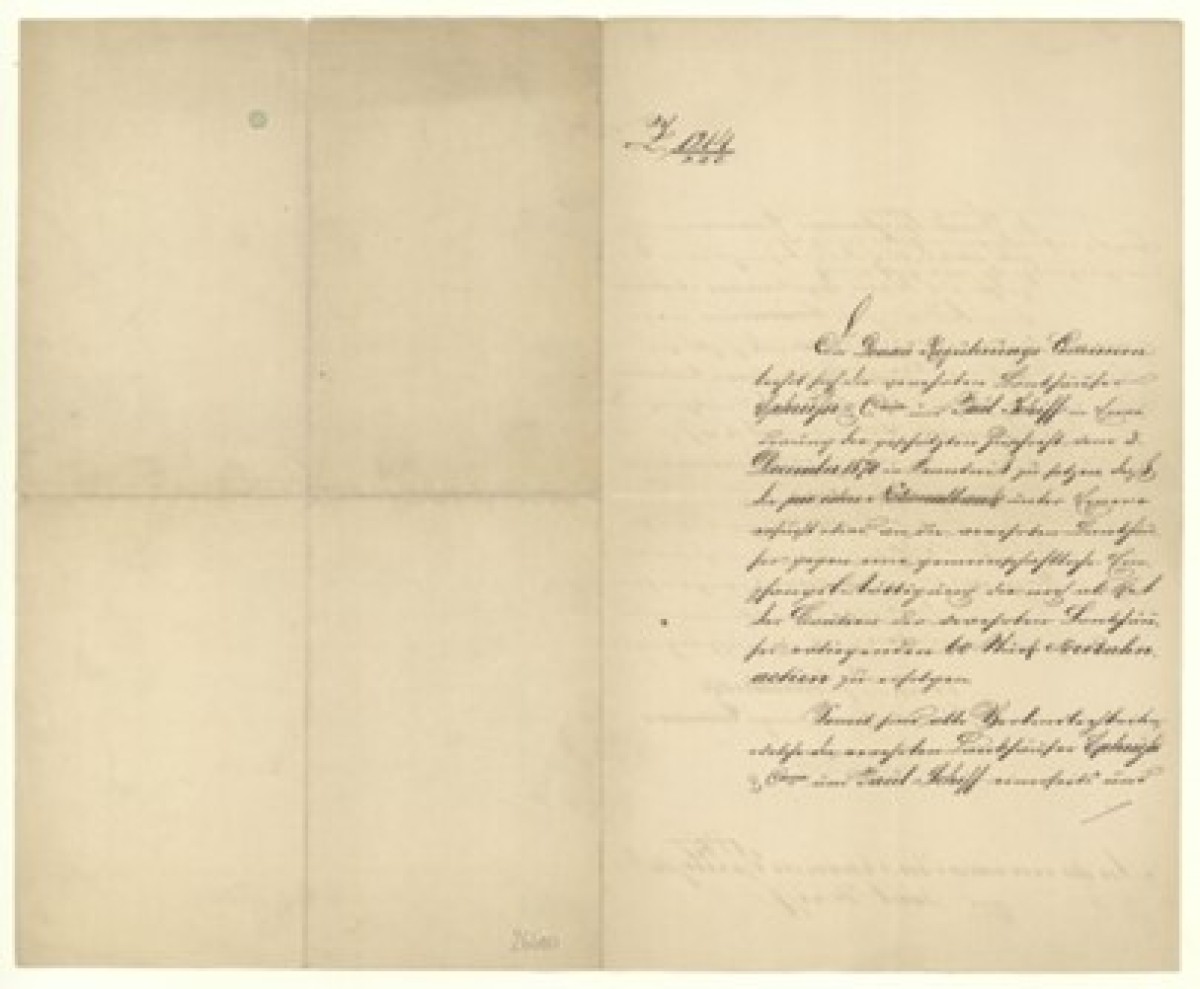

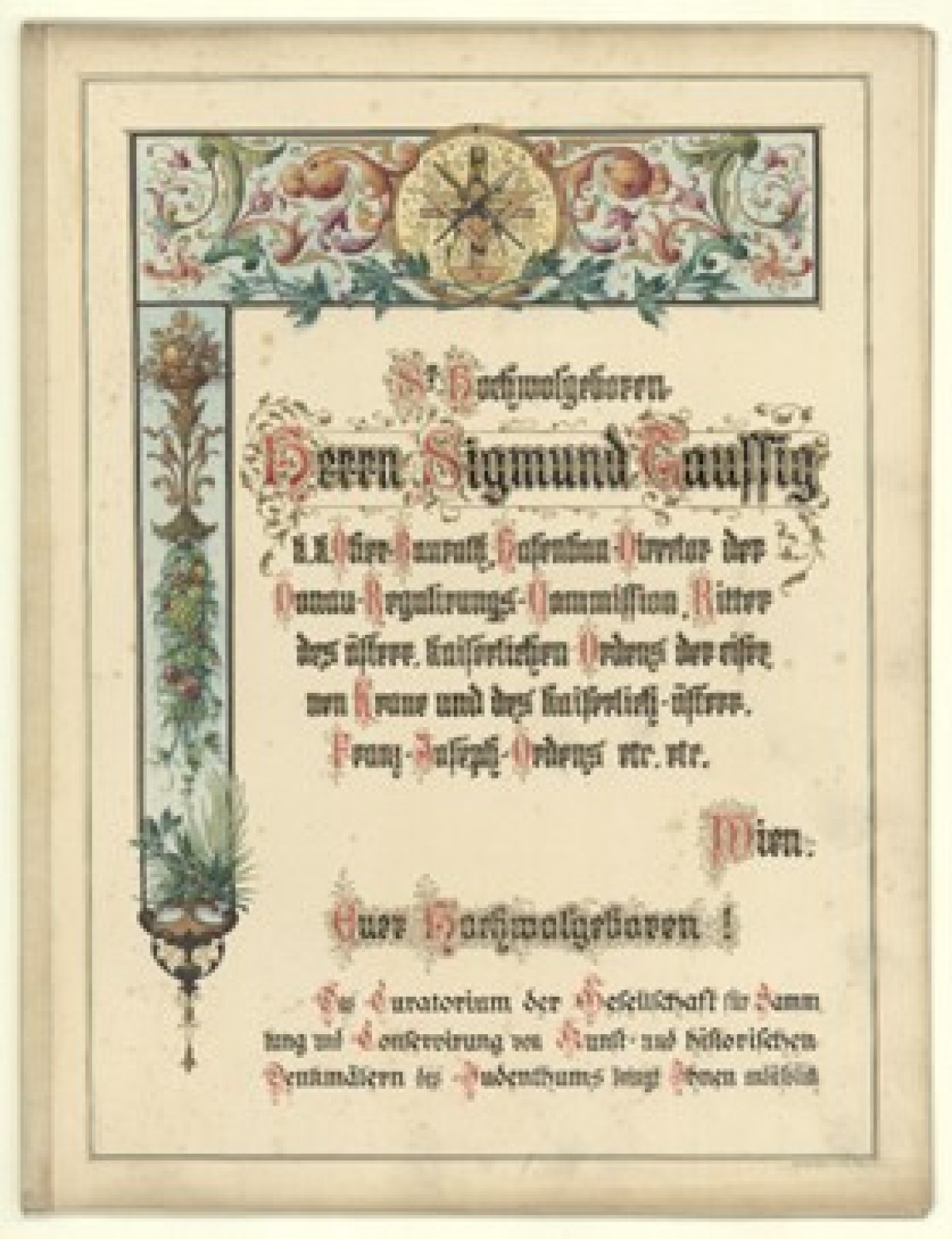

As I researched, I came across Sigmund Taussig (1840-1910), an Jewish Austrian civil engineer who helped establish the Jewish Museum of Vienna, sat on the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde (IKG, Jewish Community Organization), and worked as part of the Danube Regulation Commission. As bankers, investors and business owners, Viennese Jews contributed to the regulation in a myriad of ways such as shares in the project held by the Moritz Todesco Trust or a loan by the banking houses Ephrussi and Co. and Paul Schiff that helped finance construction.

25. June 2025

Close up

The Danube Regulation and Leopoldstadt – Peter Wildgruber’s Fulbright Research at the Jewish Museum Vienna

by Peter Wildgruber

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

Brief der Donau-Regulierungs-Commission an die Bankhäuser Ephrussi und Paul Schiff, December 7, 1870.

This letter was sent from the Commission to the banks owned by Ephrussi and Schiff to thank them for the loan that helped finance the Regulation.

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

Portrait of Sigmund Taussig

In my research, I have learned to navigate Vienna's archival resources in the Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, the Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv, the archive of the Jewish Community (IKG) and the Bezirksmuseen (district museums). During a tour of Bezirksmuseum Brigettenau’s fascinating new Donau-Raum, I learned how the Viennese have used the river for trade and recreation and how that relationship has evolved. The challenges of finding Jewish sources, reading Kurrent script, and deciphering their meanings have been especially rewarding. I am excited to continue uncovering stories as I work with the Jewish Museum for the remainder of my stay in Vienna.

Markus, David. Glückwunschadresse für Sigmund Taussig. 1900.

Sigmund Taussig received this illustrated congratulatory address for his sixtieth birthday.

© Jüdisches Museum Wien

Intern Wildgruber’s work on the Looted Books Project

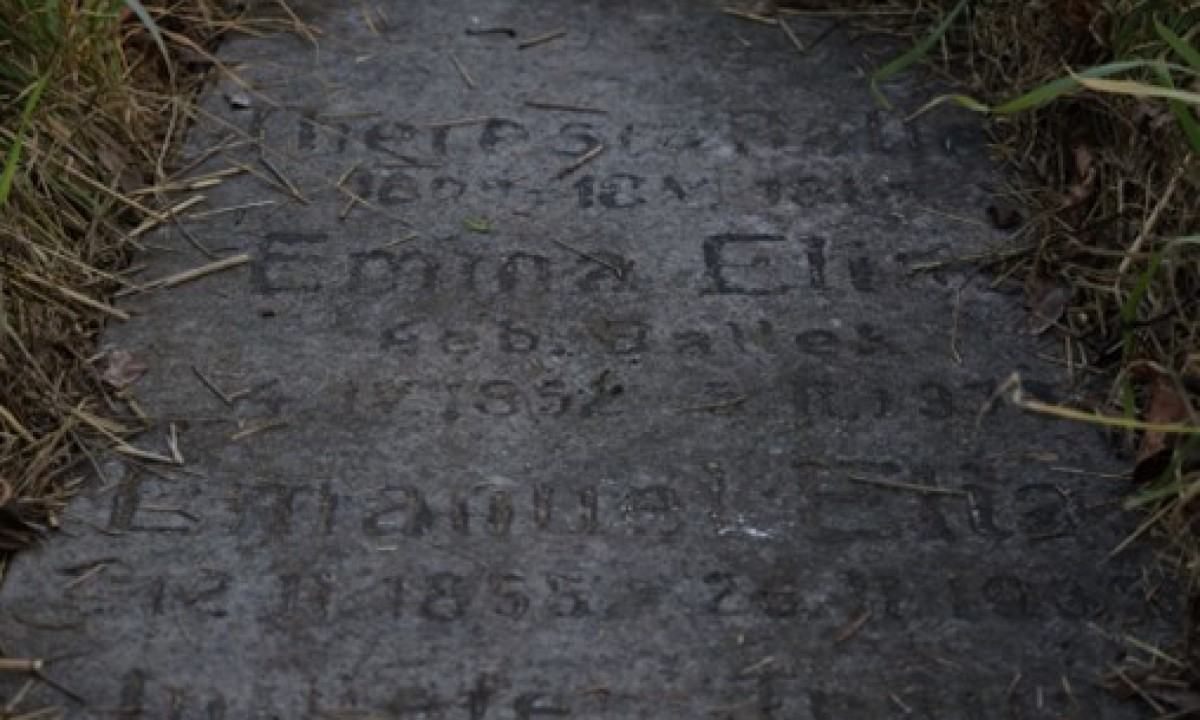

I have assisted genealogist Markus Pasterk with the Looted Books Project, by delving into the family history of the Elias’, a Jewish family in Vienna. The Looted Books Project seeks to reunite texts seized by the Nazis with their original owners and their descendants. In this case, book(s) previously owned by “Emma Elias” were confiscated and I was tasked with tracing her lineage. Using publicly-available digitized birth, marriage, and burial records, I created a family tree extending from the mid-nineteenth century to the modern day, identifying at least two living relatives.

© Peter Wildgruber

Kneeling by Emma Elias’ uncovered headstone

Vast online resources like JewishGen and FamilySearch allowed me to find abundant family records. Emma (1852-1933) was born in Boskowice, Moravia and moved to Vienna where she lived in the 9th district and began a family. I found five children born to Emma and her husband Emanuel. In 1933, she had two surviving children, Leo and Elsa, upon her passing. After living in Vienna for decades, Leo emigrated with his own son Albert to the United States while fleeing Nazi persecution. In addition, I also located the final resting places of many members of the Elias family in Vienna's Zentralfriedhof. I will never forget uncovering Emma’s buried headstone. I approximated the general area of where Emma’s plot should be but found nothing.

As I turned to leave, I noticed a patch of stone, no bigger than a cobblestone, peeking through the dry leaves. As I shifted the dirt and weeds away, a letter - then a name was revealed: Elias. There I found the plot of Emma, her mother Resi, Emanuel, and daughter Elsa. In uncovering the past, I played a small part in an initiative to restore stolen property back to their rightful owners.

© Peter Wildgruber

Headstone of the Elias family after brushing aside debris

© Peter Wildgruber

Peter recently presented his research at a Fulbright forum on Austrian Studies.

© Peter Wildgruber

Peter speaking at the event

© JMW

Curator Caitlin Gura and US Fulbright Combined Grantee Peter Wildgruber at the Jewish Museum Vienna, June 2025