Out and about in "Our City!" - Währing

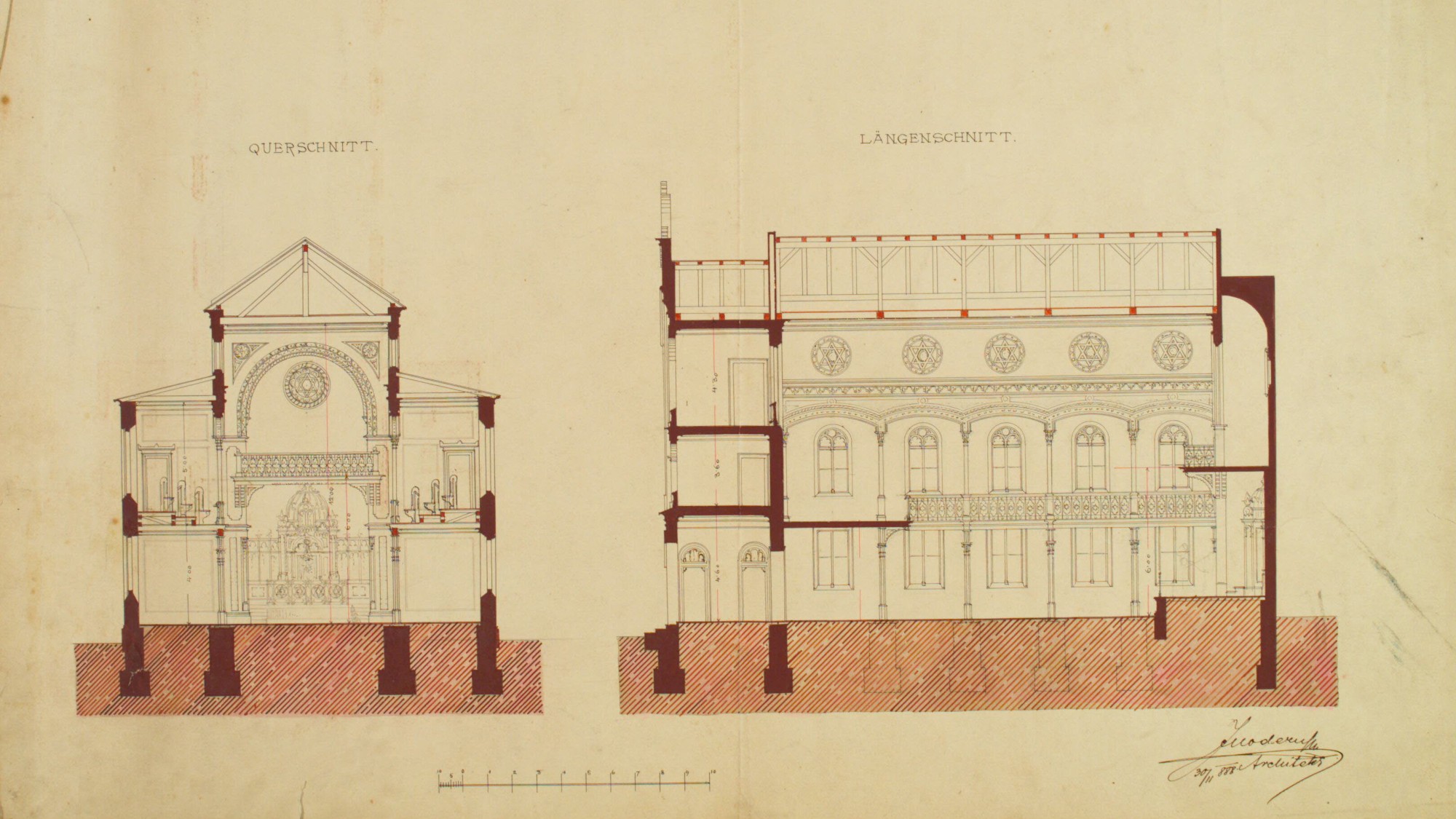

There are two drafts for the synagogue on Wienerstrasse, which has been called Schopenhauerstrasse since July 18, 1894. Planned by Jakob Modern and completed in 1889, the building featured an oriental touch on the inside and Gothic elements on the outside. This place of worship provided space for 116 women and 328 men. Nothing more is known about the second project than the date of submission, 1888, and the executing office, Ludwig Schöne, who came from Leipzig and was one of the busiest architects of the Ringstrasse era.

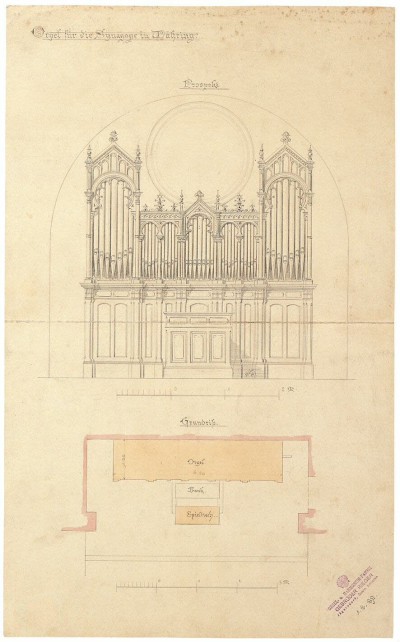

In the small community there were orthodox and liberal views, which can also be seen in an organ building project. In the second half of the 19th century, the question arose in many synagogues whether an organ – the queen of instruments – should be used, on the one hand, to accompany or arrange the congregational singing and, on the other hand, perhaps most of all, to make the receptiveness towards modernity audible and visible. The renowned and still active organ building company Rieger in Vorarlberg was commissioned with the planning. The drawing of the floor plan and prospectus from August 1, 1889 alone was time-consuming and expensive, but ultimately in vain, because orthodoxy prevailed against the installation of an organ in the 18th district.

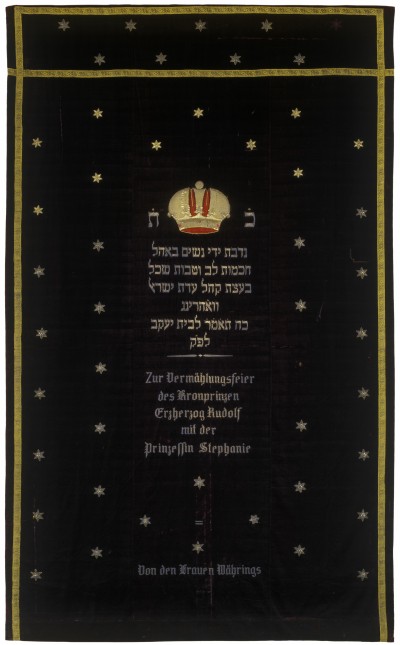

In 1881, before the synagogue was built, a Torah curtain (Hebrew: parocheth) had been crafted. Donated for the marriage of Crown Prince Rudolf and Princess Stephanie of Belgium, it was used in the prayer house of the district. A parocheth hangs in front of the Aron ha-Kodesch, the “Holy Ark” in which the Torah scrolls are stored when they are not being read from. It is interesting that the dedication is also made in German. “For the wedding celebration of Crown Prince Archduke Rudolf and Princess Stephanie. From the women of Währing.” The technical specifications in the museum inventory offer information about the material, size and condition. Silk velvet, tinsel, silver foil, bouillon threads, gold braid and brown-purple chintz went into making the richly ornamented curtain. Measuring 223 x 135 cm, the textile was restored in 1995. The “women of Währing” probably refers to the Währing Women’s Charity Association based at Schopenhauerstrasse 39.

Many objects in the Jewish Museum Vienna collection show that religion and patriotism or loyalty do not have to stand in each other’s way. Beside their interesting details in terms of art history, all of them express a deep sense of belonging – to the imperial family, to the monarchy, to the home one had been cheated out of since the spring of 1938 at the latest. Franz Modern, the grandson of the architect of the synagogue at Schopenhauerstrasse 39, was a doctor and fled with his wife to Shanghai, where his daughter Elisabeth was born in 1941. Dr. Modern wanted to do everything right and reported Elisabeth’s birth not only to the Jewish community, but also to the German consulate. Since Elisabeth cannot possibly be a Jewish name, her name was Rachel on the paper. For that which must not, cannot be.

Even before the synagogue was constructed in Währing, a Jewish cemetery had existed at what is Schrottenbachgasse 3 today. From 1784 onwards, this was the main burial place of the Jewish Community of Vienna for a long time. Funerals were held there until 1911, and the tombstones have both Hebrew and German inscriptions. A total of three exhumations took place during the Nazi period. Not all mortal remains were buried in Vienna’s Central Cemetery at their hopefully truly final resting place.

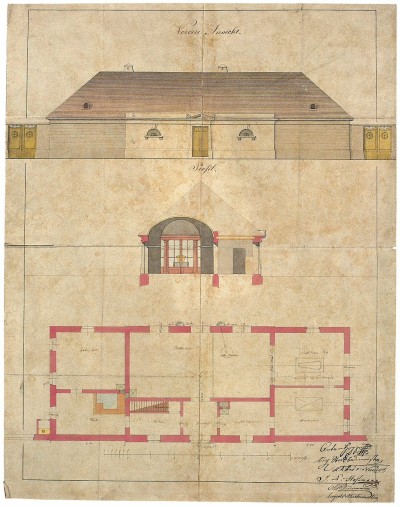

The Tahara House, ascribed to the architect Josef Kornhäusl, consisted of rooms intended for those to be buried, a “guard room,” a “wash room” and a room for the “viewing space during the funeral address,” which could be seen from the outside, as well as a small apartment for the cemetery employee. The plan was signed by an official of the municipal building authorities as well as by representatives of the Viennese Jewish community (Isak Löw Hofmann, Michael Lazar Biedermann and Leopold Wertheimstein). In 2012, the building was renovated and a prayer room added.