Paul Peter Porges Sweater embroidered with his initials gifted by his grandmother in 1939

04. July 2025

Close up

Paul Peter Porges’ Sweater: A Quiet Companian in Turbulent Times

by Violeta Villacorta-Apaza

It’s common for us to occasionally clean out our closets, putting away clothes we no longer wear, whether because they’re old, no longer our style, or simply don’t fit anymore. So why would someone hold onto a sweater from childhood until the end of their life? Why would it become part of a museum collection? These were the questions that came to mind when I saw the bright red knitted sweater with the letters “PPP.” It reminded me of the one Molly Weasley gave to Harry Potter: handmade, personal, and filled with love. But this sweater was given to Paul Peter Porges by his grandmother before he left Vienna on a Kindertransport. It is much more than a piece of clothing. It is a quiet companion, a symbol of resilience, love, and memory. Unlike many objects that are eventually discarded, this sweater was carried across borders, through danger and displacement.

Born in Vienna in 1927, Porges grew up during the rise of Nazi persecution. After the 1938 Anschluss of Austria to Nazi Germany, antisemitic laws escalated, placing Jewish families like his in grave danger. In 1939, at the age of twelve, he was sent to France alone on a Kindertransport. The red sweater was one of the few possessions he took with him, a tangible link to his family and past.

But the journey to safety was far from a good experience for a little PPP. Upon arrival at the Rothschild Hospital in France, Porges faced a sudden new reality:

“For me this change was terrible and brutal. Strangers who spoke a different language went through our small suitcases and rucksacks and removed items they considered unnecessary! My new underwear, a schnitzel sandwich, the last link to Resi (the nanny) were taken from me. The shock was enormous - I cried the whole night in my hospital bed.”

Born in Vienna in 1927, Porges grew up during the rise of Nazi persecution. After the 1938 Anschluss of Austria to Nazi Germany, antisemitic laws escalated, placing Jewish families like his in grave danger. In 1939, at the age of twelve, he was sent to France alone on a Kindertransport. The red sweater was one of the few possessions he took with him, a tangible link to his family and past.

But the journey to safety was far from a good experience for a little PPP. Upon arrival at the Rothschild Hospital in France, Porges faced a sudden new reality:

“For me this change was terrible and brutal. Strangers who spoke a different language went through our small suitcases and rucksacks and removed items they considered unnecessary! My new underwear, a schnitzel sandwich, the last link to Resi (the nanny) were taken from me. The shock was enormous - I cried the whole night in my hospital bed.”

© JMW

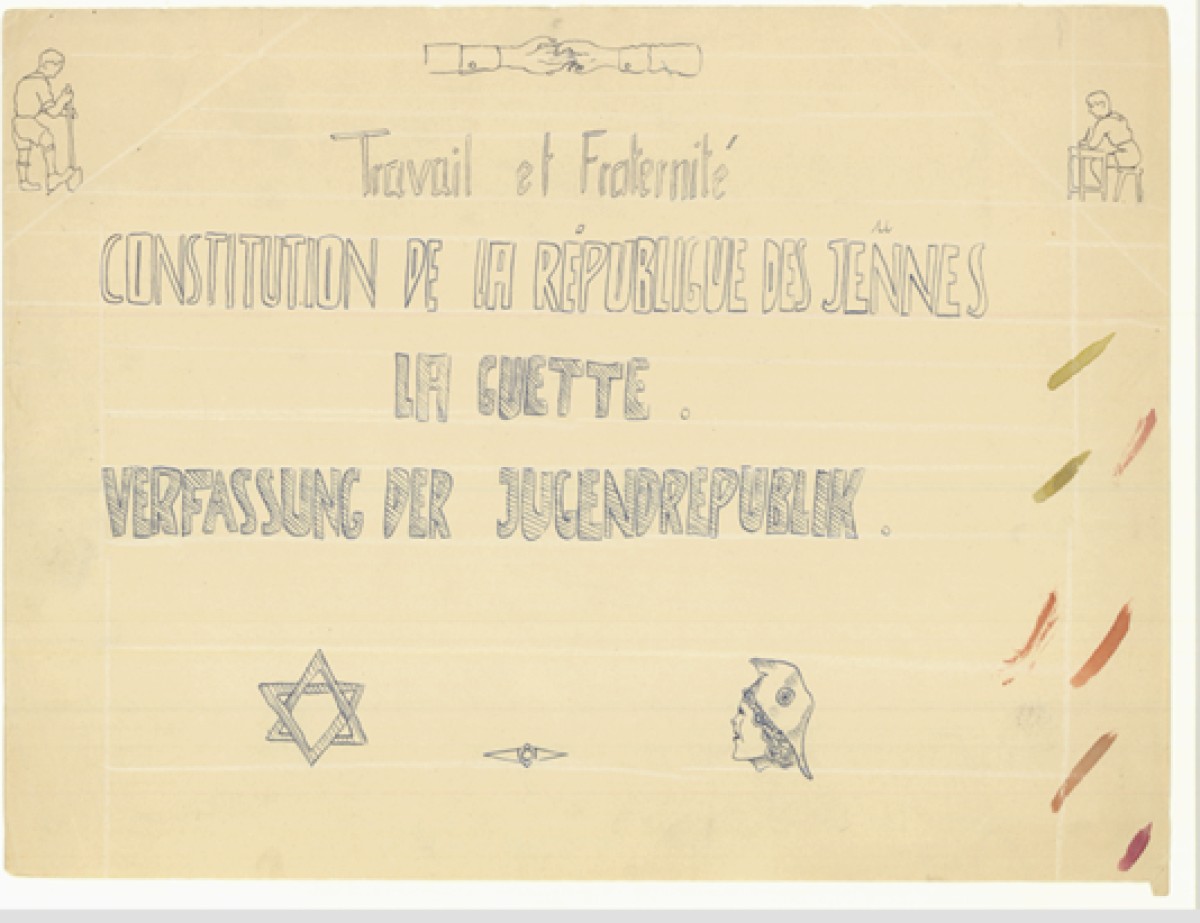

Drawing by PPP featuring symbolic representations of the values and principles at the Children's Republic of La Guette in German and French, c. 1940

In France, Porges found refuge at the Children’s Republic of La Guette, a progressive educational community housed at the Château de la Guette provided by the Rothschild family. It offered Jewish refugee children an unusual sense of agency, operating on democratic principles that allowed them to participate in daily decision making.

Even amid uncertainty, Porges kept drawing, using his art to document life at La Guette and to process his experiences. “I always used to draw and in La Guette I was the illustrator. If anyone ever wanted anything drawn, or someone had to draw something, they came to PPP. PPP drew for family albums, PPP drew the souvenirs, the things, the posters, all these things.”

Through his early sketches, Porges captured moments of both fear and hope. His drawings served as testimony to a generation of children separated from their families in a desperate attempt to survive. Parents unable to guarantee the safety of their family placed their trust in this journey, not knowing if they would ever see their children again.

Even amid uncertainty, Porges kept drawing, using his art to document life at La Guette and to process his experiences. “I always used to draw and in La Guette I was the illustrator. If anyone ever wanted anything drawn, or someone had to draw something, they came to PPP. PPP drew for family albums, PPP drew the souvenirs, the things, the posters, all these things.”

Through his early sketches, Porges captured moments of both fear and hope. His drawings served as testimony to a generation of children separated from their families in a desperate attempt to survive. Parents unable to guarantee the safety of their family placed their trust in this journey, not knowing if they would ever see their children again.

© JMW

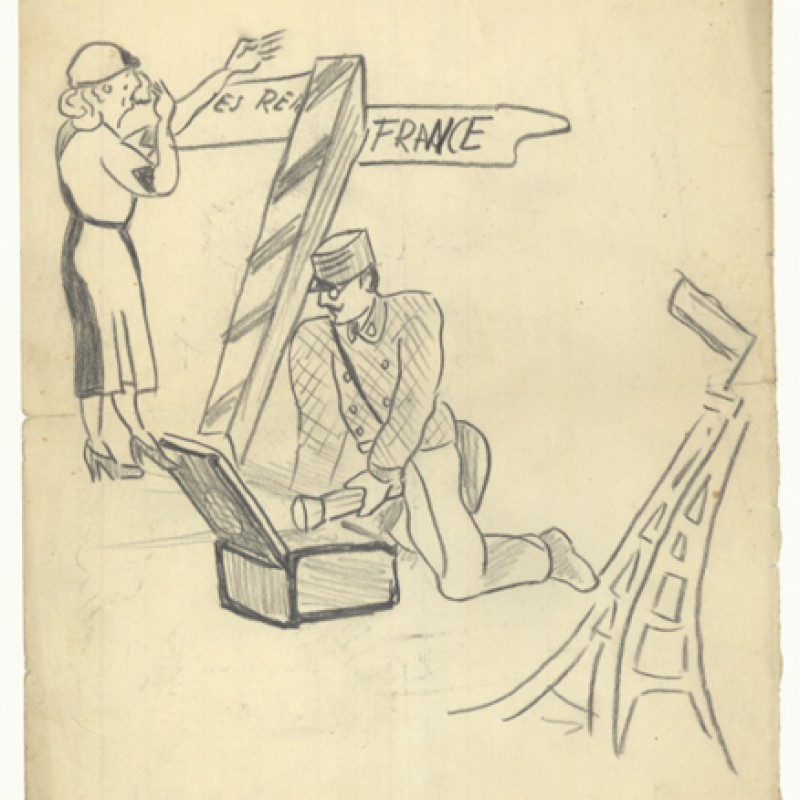

PPP’s sketch showing a crying woman pointing to a "FRANCE" signpost while a man inspects a suitcase, with the Eiffel Tower in the background, c. 1940

© JMW

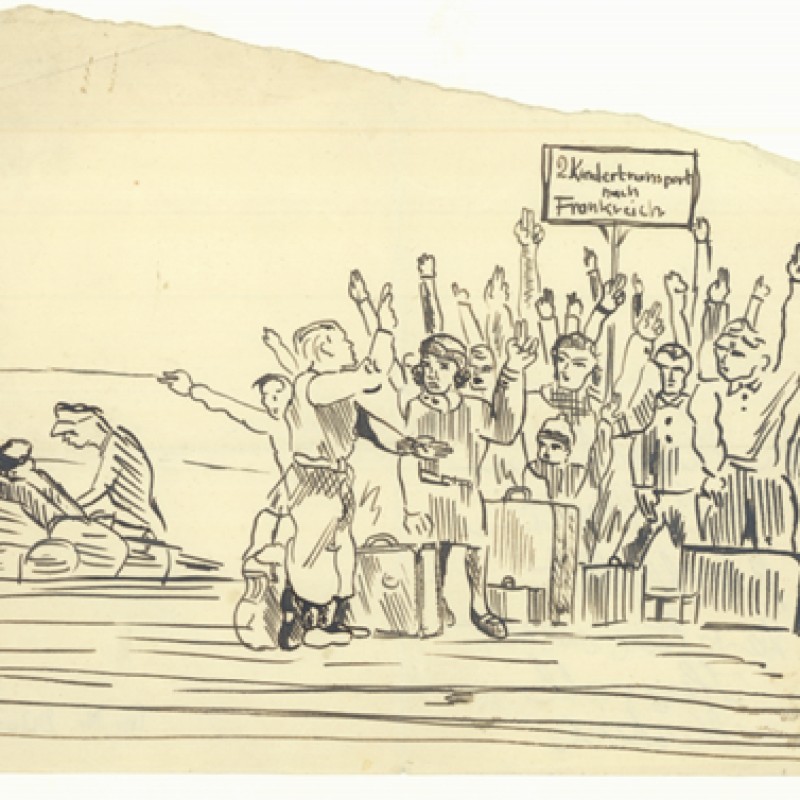

Families gathered at a train station in Vienna, saying goodbye to the children leaving for France on a Kindertransport, illustrated by PPP, c. 1939

The plan to follow them as soon as possible did not always work out, and many parents were deported and murdered. The Kindertransports saved a large number of children, but as a result they had a childhood without a home and mostly without a family.

What makes these moments even more impactful is that they were recorded through the eyes and hands of a child. Even at a young age, Porges was not only living history, but documenting it through his art. His drawings, simple yet profound, now serve as both personal and historical testimony, giving voice to an experience shared by many.

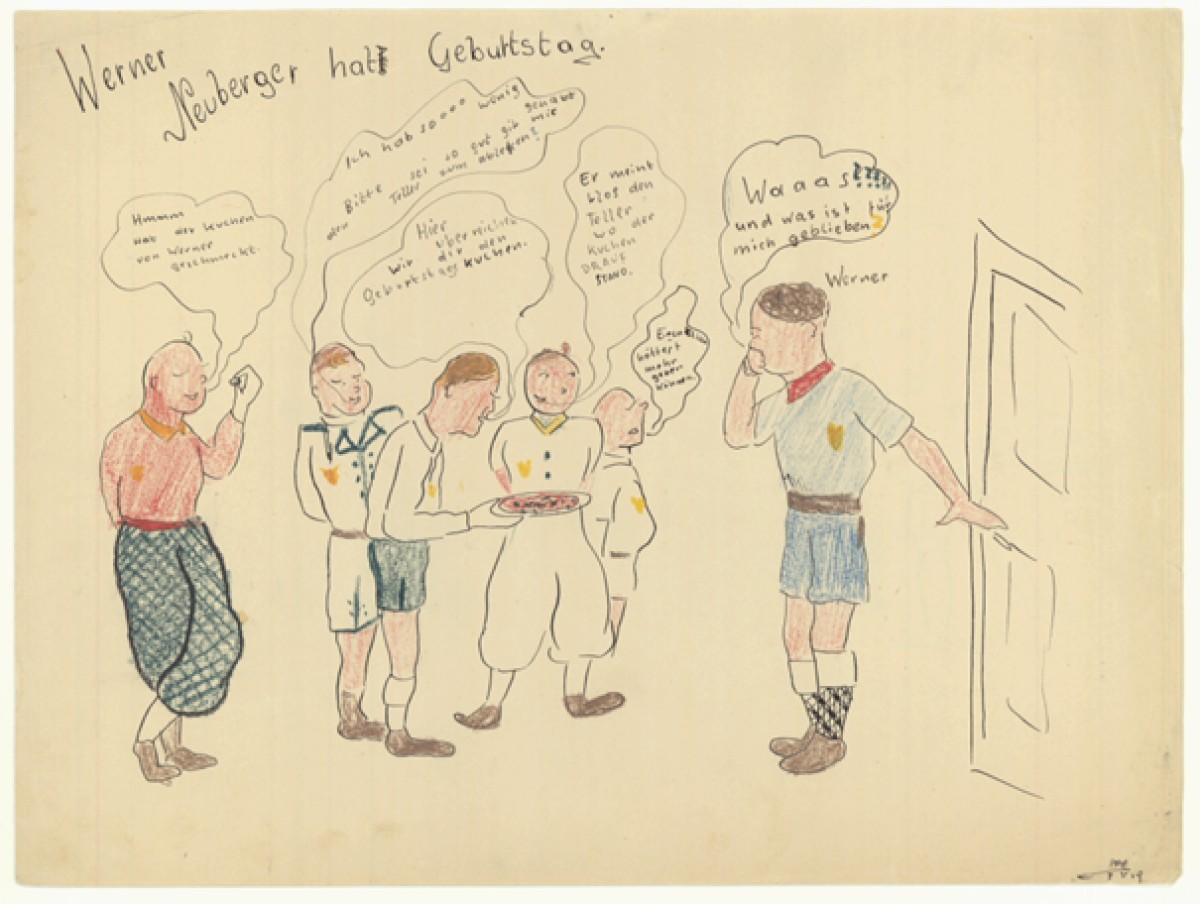

In his illustrations, young Porges captured the emotional complexity of these experiences: leaving home, living among strangers, finding new rhythms in daily life. In one drawing, he depicted a moment at La Guette: children gathered together, forging new bonds in a foreign country. Despite their new reality, they found strength in community. These strangers became a kind of chosen family.

What makes these moments even more impactful is that they were recorded through the eyes and hands of a child. Even at a young age, Porges was not only living history, but documenting it through his art. His drawings, simple yet profound, now serve as both personal and historical testimony, giving voice to an experience shared by many.

In his illustrations, young Porges captured the emotional complexity of these experiences: leaving home, living among strangers, finding new rhythms in daily life. In one drawing, he depicted a moment at La Guette: children gathered together, forging new bonds in a foreign country. Despite their new reality, they found strength in community. These strangers became a kind of chosen family.

© JMW

A comical birthday celebration scene at La Guette, illustrated by PPP, 1939

© JMW

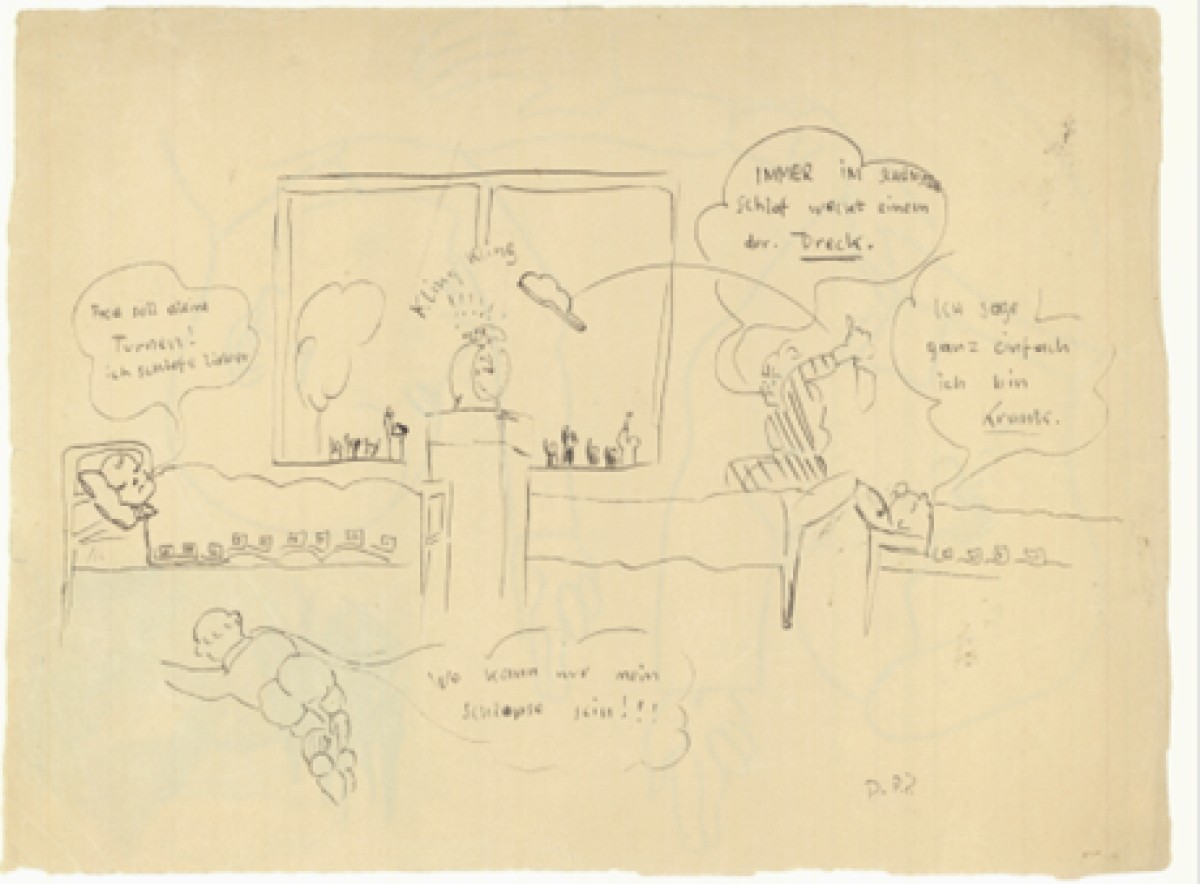

Children in La Guette waking up in the morning together, c. 1940

© JMW

The illustrated daily life at the Children's Republic of La Guette by PPP, c. 1940

© JMW

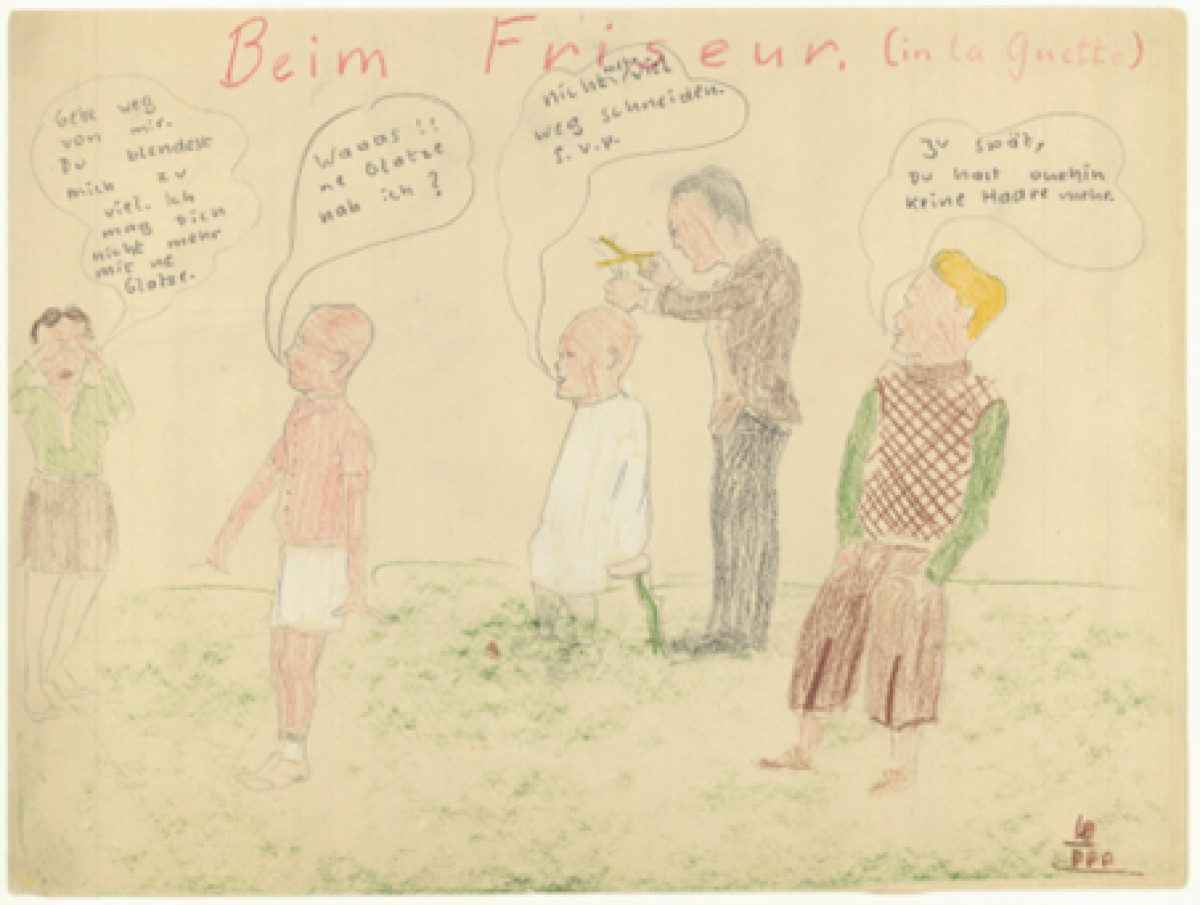

Getting a bad haircut in La Guette illustrated by PPP, 1940

Porges’ red sweater, simple, handmade, and marked with his initials remained a constant, a thread of continuity within uncertainty. It was more than clothing, it provided comfort in the unfamiliar, just as the children at La Guette found comfort in routine and each other.

In 1942, as the situation worsened under German occupation, Porges escaped to Switzerland. There he attended art school in Geneva improving his artistic skills. He also met Lucy, who would become his life partner.

After the war, he reunited with his surviving family in the United States and began a new chapter. Porges served in the U.S. Army, where he contributed cartoons to Stars and Stripes, a military publication. This early work helped shape his artistic voice, which he continued to refine in New York. His cartoons later appeared in Mad Magazine, The New Yorker, and The Saturday Evening Post, where his humor and style reached a wider audience. As he looked back on his journey, he once said, “While I was fleeing, of course, I didn’t draw. But I always somehow knew that my life would somehow be involved with drawing.” That sense of inner certainty stayed with him throughout his journey from his starting point in Vienna to New York.

With the red sweater he never let go of, with the sketches he made as a child, Porges made his journey tangible. Porges never stopped using art to make sense of the world. From an early age, Porges used drawing as a way to interpret and share his world. This deep connection to art stayed with him, evolving into a defining aspect of his identity and career. His journey from a young Jewish boy escaping Nazi persecution to a celebrated cartoonist, demonstrates the power of art as both a means of survival and a driver for life.

The sweater, now preserved in the Jewish Museum Vienna, is a testament to how everyday objects can become vessels of memory. It embodies the love of a grandmother, the pain of separation, and the strength of survival. Just like the drawings Porges made throughout his life, it tells a story far greater than itself.

Reading Porges’ story, I couldn’t help but think of my own journey. Four years ago, I left my home country alone. Since then, I’ve been moving constantly, across cities, countries, and phases of life. With each move, there’s always something I’ve had to leave behind. But I’ve never once considered getting rid of the gifts from my parents: the scarf my dad gave me, the blouses my mom picked for me. Since I understand the feeling that these are not just items of clothing. They are reminders of love, of presence across distance, of care that is present even when people can’t be near. Like Porges’ red sweater, these objects stay with me. They are reminders of love and familiarity, offering a sense of continuity in a life shaped by movement.

In 1942, as the situation worsened under German occupation, Porges escaped to Switzerland. There he attended art school in Geneva improving his artistic skills. He also met Lucy, who would become his life partner.

After the war, he reunited with his surviving family in the United States and began a new chapter. Porges served in the U.S. Army, where he contributed cartoons to Stars and Stripes, a military publication. This early work helped shape his artistic voice, which he continued to refine in New York. His cartoons later appeared in Mad Magazine, The New Yorker, and The Saturday Evening Post, where his humor and style reached a wider audience. As he looked back on his journey, he once said, “While I was fleeing, of course, I didn’t draw. But I always somehow knew that my life would somehow be involved with drawing.” That sense of inner certainty stayed with him throughout his journey from his starting point in Vienna to New York.

With the red sweater he never let go of, with the sketches he made as a child, Porges made his journey tangible. Porges never stopped using art to make sense of the world. From an early age, Porges used drawing as a way to interpret and share his world. This deep connection to art stayed with him, evolving into a defining aspect of his identity and career. His journey from a young Jewish boy escaping Nazi persecution to a celebrated cartoonist, demonstrates the power of art as both a means of survival and a driver for life.

The sweater, now preserved in the Jewish Museum Vienna, is a testament to how everyday objects can become vessels of memory. It embodies the love of a grandmother, the pain of separation, and the strength of survival. Just like the drawings Porges made throughout his life, it tells a story far greater than itself.

Reading Porges’ story, I couldn’t help but think of my own journey. Four years ago, I left my home country alone. Since then, I’ve been moving constantly, across cities, countries, and phases of life. With each move, there’s always something I’ve had to leave behind. But I’ve never once considered getting rid of the gifts from my parents: the scarf my dad gave me, the blouses my mom picked for me. Since I understand the feeling that these are not just items of clothing. They are reminders of love, of presence across distance, of care that is present even when people can’t be near. Like Porges’ red sweater, these objects stay with me. They are reminders of love and familiarity, offering a sense of continuity in a life shaped by movement.

© JMW

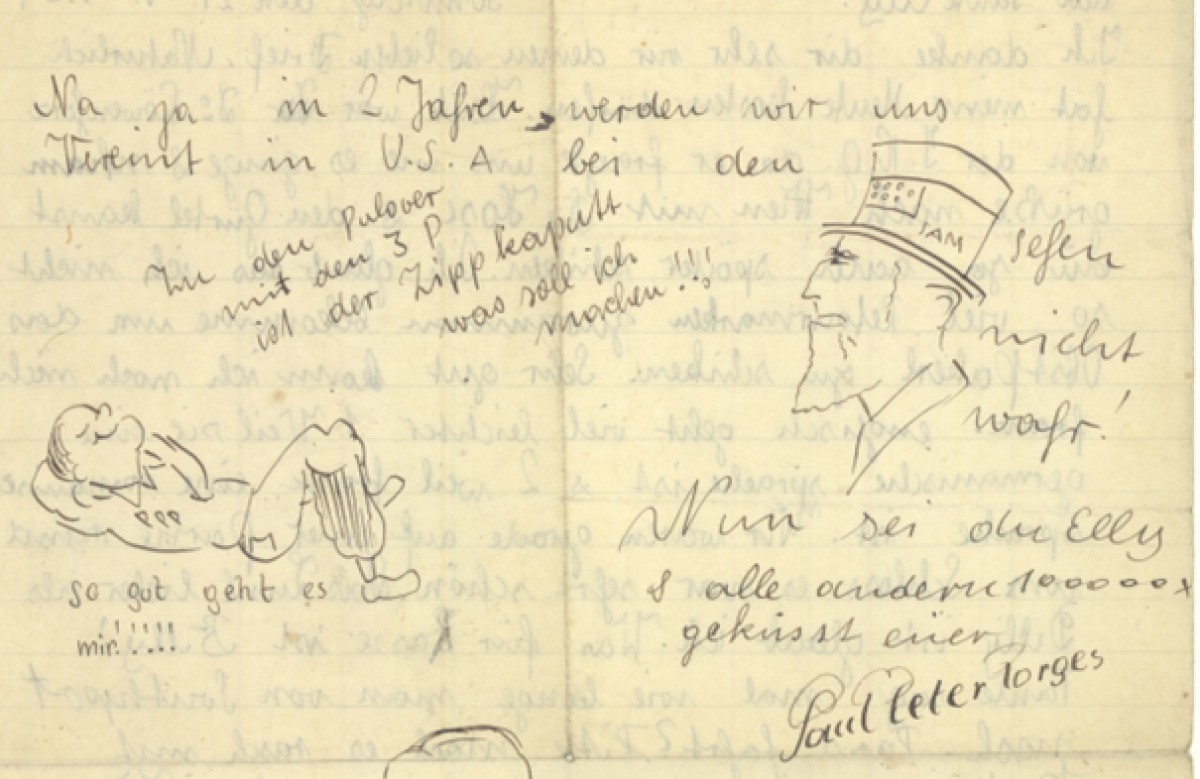

PPP’s letter to his aunt from La Guette mentioning his sweater gifted by his grandmother. The zipper was broken and he didn’t know how to fix it, 1939

© JMW

Intern Violeta Villacorta-Apaza and Curator Caitlin Gura at the Jewish Museum Vienna, May 2025

About the Author: Violeta Villacorta-Apaza is a Human Rights major at Trinity College (CT). She wrote this piece during her 2025 Spring semester college internship at the Jewish Museum Vienna.

The papers and works of Paul Peter Porges and his wife Lucie Porges were donated to the Jewish Museum Vienna in 2015. Paul Peter Porges’s red sweater is on display at in museum’s permanent exhibition at Dorotheergasse 11. His story continues to inspire visitors to this day.

The PPP quotes are from an interview conducted by Werner Hanak and Natalie Lettner with Paul Peter Porges in 1998 in preparation for the exhibition Style and Humor: Lucie and Paul Peter Porges for the Jewish Museum Vienna (JMW)

Links:

The PPP quotes are from an interview conducted by Werner Hanak and Natalie Lettner with Paul Peter Porges in 1998 in preparation for the exhibition Style and Humor: Lucie and Paul Peter Porges for the Jewish Museum Vienna (JMW)

Links: