While the eagerly awaited European Men’s Soccer Championship is being celebrated these days in a corona-compliant manner, the Austrian female footballers are preparing for their appearance at the UEFA European Women’s Soccer Championship in England next year. Since the highly successful premiere of the women in 2017, when the Austrian national team reached the semifinals, women’s soccer has received increasing attention in this country. However, the history of the Viennese female pioneers of the interwar period is completely buried, as the official records of Austrian women’s soccer only began in the 1970s with local championship competitions.

When soccer activities in Vienna began to professionalize in the 1920s, journalists from various newspapers called on women to try their hand at this male sport, which was becoming a mass phenomenon. The one or the other match was then reported in a humorous and sometimes derogatory manner. Women playing soccer remained a curiosity for a long time; just the word “Fußballerin” alone caused many a temper to flare. While Austrian female athletes in other sports, such as swimming, fencing or figure skating, were among the world’s best in the interwar period and were highlighted in the media for their achievements, there seemed to be no place for girls and women in soccer.

06. July 2021

Close up

After the men’s European championship is before the women’s European championship - a look forward with a look back

by Agnes Meisinger

It is all the more astonishing that the founding of the 1st Viennese Women’s Soccer Club “Kolossal” by the 22-year-old Vienna native Edith Klinger in 1934 came at a time when the Austro-Fascist regime was striving to gain state control over the sporting agenda and force women out of high-performance and competitive sports. Klinger persistently recruited women for her idea via newspaper advertisements, which led to a flood of membership applications and the establishment of further teams. After months of serious preparation, the first official women’s soccer match took place in October 1935 on Lehrerplatz in Hernals to a crowd of 2,600 spectators.

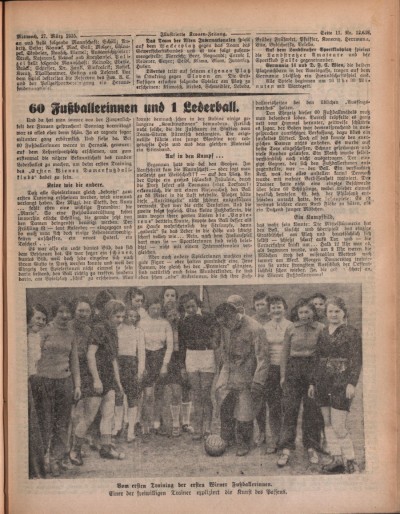

Browse through the "Kronen Zeitung" from March 27, 1935 here

Browse through the "Kronen Zeitung" from March 27, 1935 here

© ANNO_Nationalbibliothek

© JMW

Jewish female and male sports officials and the Sportclub Hakoah, which was well-known far beyond the country’s borders, contributed significantly to the development of modern sports in Vienna in the interwar period. In 1925, the Hakoah male kickers celebrated the greatest triumph in their history by winning the Austrian championship. Although there was no women’s soccer team within the Hakoah organization, the 1st Austrian Women’s Soccer Union (DFU) was founded in 1936 with the financial support of the prominent Jewish department store owner and fashion designer Ella Zirner-Zwieback. With the creation of the league, the only regulated championship operation for women in the world existed in Austria, which the trained pianist was also president of. With her entrepreneurial and social commitment, Ella Zirner-Zwieback forged ahead in a male domain not only in her professional life, but also in the world of sports.

Nine teams took part in the first season, all of them from the greater Vienna area. But even before the first game could be played, the Austrian Football Association (ÖFB) intervened by prohibiting women’s teams from using association spaces. Despite this massive exclusionary measure, the DFU managed to carry out two full championship seasons.

In the following years, the media representation of the girls and women playing soccer was ambivalent, varying between recognition and rejection: On the one hand, the female soccer players were shown respect and game dates were advertised. On the other hand, the articles often degenerated into mockery, ridiculing the achievements of the women athletes with subtle references to the biological differences between women and men. This fact promoted the transmission and consolidation of gender stereotypes in sport which occasionally have an impact even today.

In the end, the early aspirations of the Viennese women soccer players merely remained an attempt to emancipate themselves in the realm of sports. Male officials or coaches repeatedly interfered, thus undermining women’s attempts to organize themselves. Moreover, the female athletes did not correspond to the prevailing image of women, which was supposed to reflect grace and aesthetics. They were frequently exposed to journalistic malice and denied the support of the ÖFB. When the National Socialists ascended to power and women’s soccer was banned in 1938, their ambitions came to an abrupt end. A little later, Ella Zirner-Zwieback, whose fashion house “Maison Zwieback” on Kärntner Strasse had been “Aryanized,” fled from racist persecution to the USA with her son Ludwig. After the end of the war, it took several decades until women’s soccer could be reorganized in the Second Republic. Following a ban on practicing and playing, as well as the deliberate negation by the ÖFB, women’s soccer was finally recognized and institutionally anchored in 1982.

Literature tips:

Astrid Peterle (ed.), Buy From Jews! Story of a Viennese store culture, catalog for the exhibition of the same name held at the Jewish Museum Vienna in 2017, Vienna: Amalthea Signum Verlag, 2017.

Helge Faller/Matthias Marschik, Eine Klasse für sich. Als Wiener Fußballerinnen einzig in der Welt waren, Vienna: Verlagshaus Hernals, 2020.

Astrid Peterle (ed.), Buy From Jews! Story of a Viennese store culture, catalog for the exhibition of the same name held at the Jewish Museum Vienna in 2017, Vienna: Amalthea Signum Verlag, 2017.

Helge Faller/Matthias Marschik, Eine Klasse für sich. Als Wiener Fußballerinnen einzig in der Welt waren, Vienna: Verlagshaus Hernals, 2020.

© wulz.cc