Brigitte (Britta) Reinhilde Lamberg was born on June 13, 1927, in Vienna, the only daughter of lawyer Dr. Ernst Moritz Lamberg (born April 19, 1888, Frýdek-Místek) and his wife Louise (née Schapira, July 14, 1901, Hamburg).

05. May 2025

Expo Window

Expo Window: Liberation Day – Mauthausen

by Daniela Pscheiden

Britta Lamberg, Vienna, circa 1942

Louise Lamberg, Vienna, 1939

Ernst Lamberg, Vienna, 1939

For the first eight years of her life, Britta Lamberg lived with her family at Türkenschanzplatz 7 in Vienna’s 18th district. Her earliest memories are of Türkenschanz Park with its playgrounds, swans, and impressive weeping willows. Both her mother and her nanny took her out a lot, and she describes her childhood as extremely happy.

While her father worked as a lawyer, her mother was involved in Jewish charitable organizations. Attending the first grade of elementary school, Britta Lamberg vividly remembers the morning “Our Father” prayers and the subsequent making the sign of the cross.1 It wasn’t until a teacher asked her to stop doing this that she first became aware of her Jewishness. In 1935, the Lambergs moved into an apartment at Esslinggasse 18 in Vienna’s 1st district.2

At the new elementary school on Concordiaplatz, she was no longer the sole Jewish child. She took religious education classes, attended the youth service at the Seitenstettengasse Temple, and insisted that Hanukkah be celebrated at home instead of putting up a Christmas tree. Although her parents were not religious, they always went to the Temple on the High Holidays. In the 1937/38 school year, she transferred to the Rahlgasse Grammar School, where she first experienced antisemitism after the Anschluss of Austria in 1938. Children who had previously been her friends now blocked the entrance to the classroom or threw stones at their Jewish classmates in the street. After completing her first year, she had to transfer to the Zwi Perez Chajes Grammar School. One of her classmates was Armin Rothstein, nicknamed Flips, who became known throughout Austria after the war as the clown Habakuk.

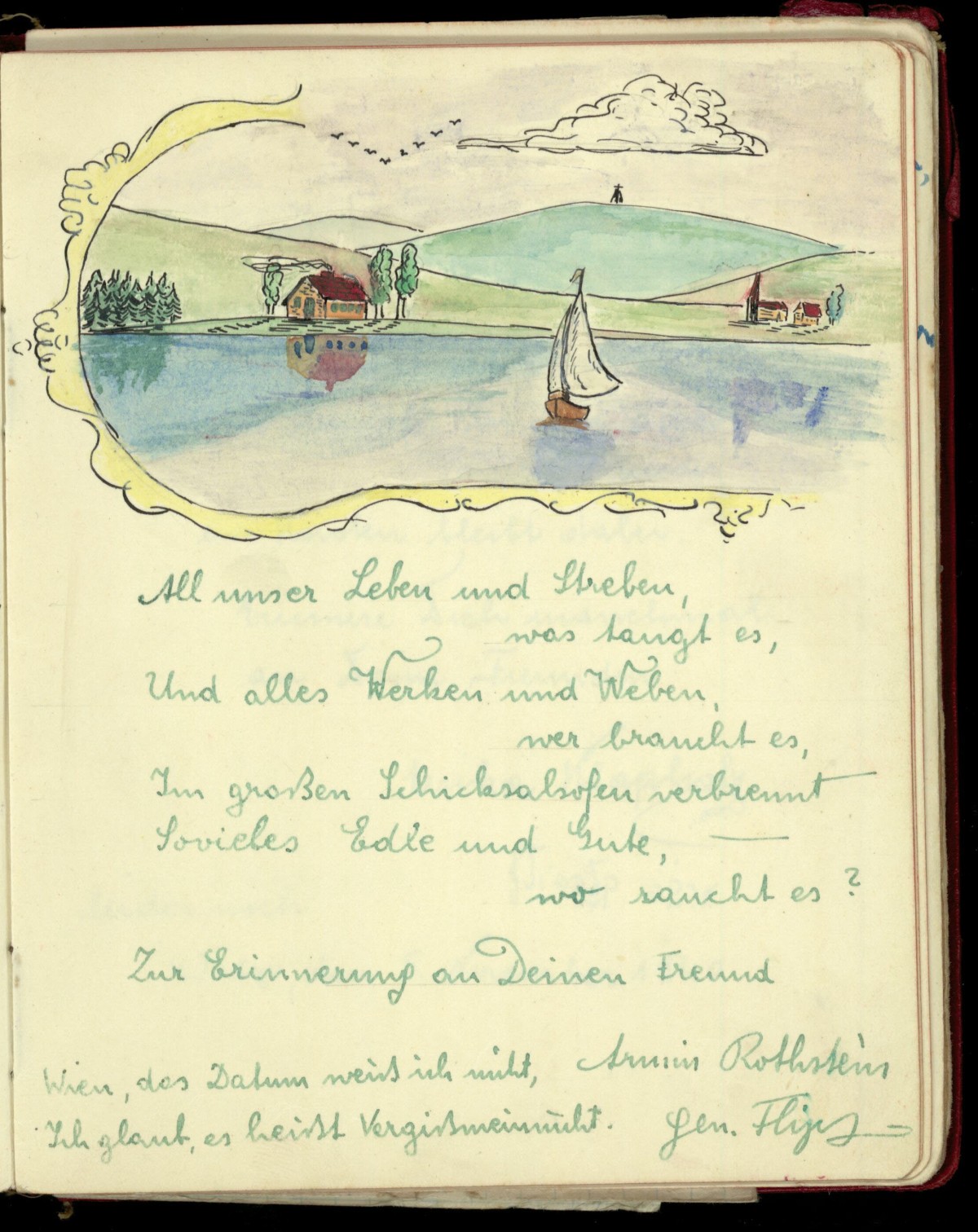

Entry by Armin Rothstein in Britta Lamberg’s poetry album, circa 1940

Armin Rothstein on a card with a dedication to Britta Lamberg in 1945 as a magician

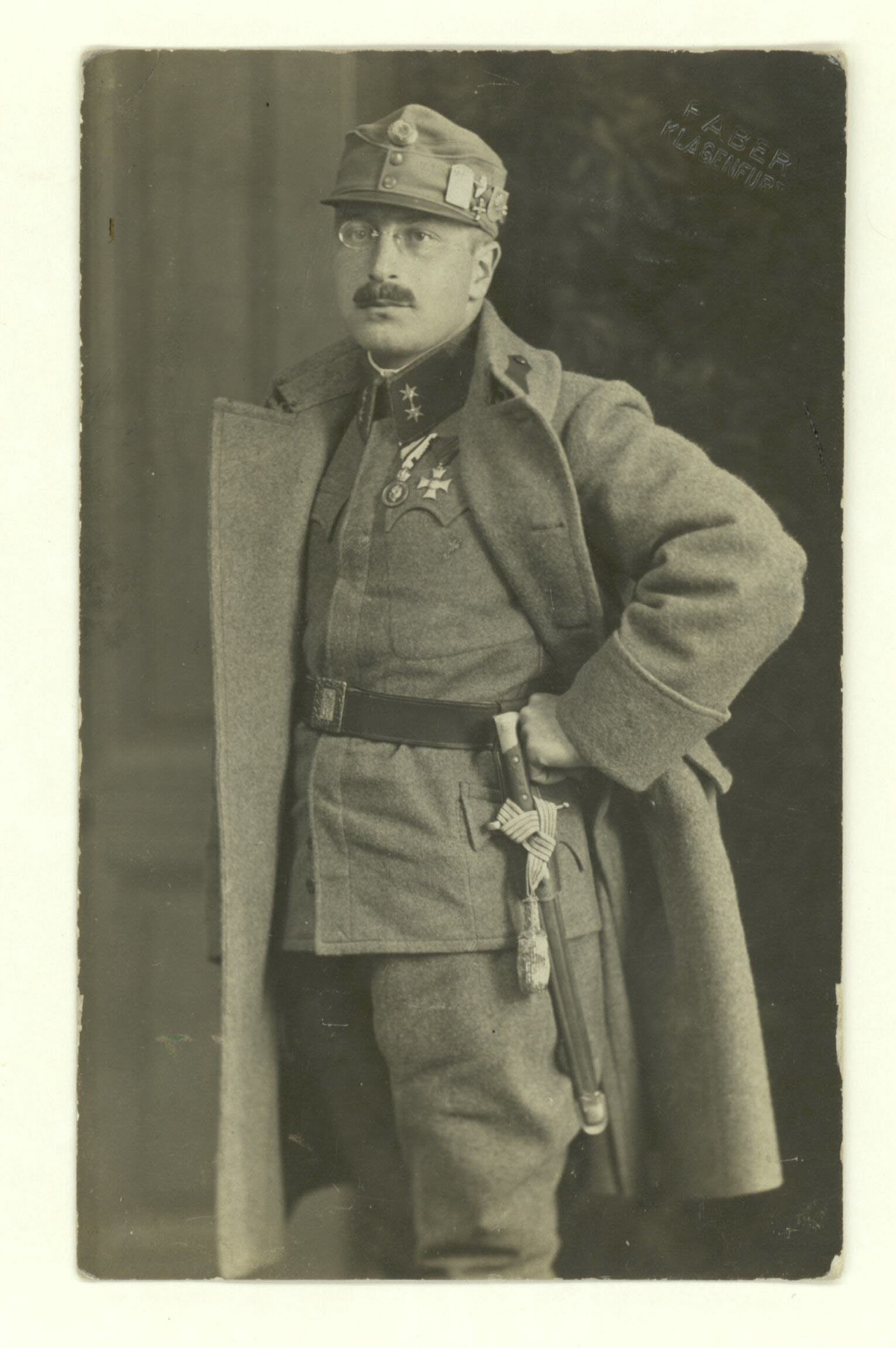

Britta Lamberg’s father remained optimistic for a long time. As a highly decorated World War I veteran, he felt completely Austrian.3

From 1939 onwards, however, he and his family also attempted to emigrate to England, Australia, or the USA. Unfortunately, all efforts failed.4 Britta Lamberg herself described wearing the Star of David as “odd.” She and her friends often circumvented access restrictions to parks or cinemas by covering the Star of David with a bag or scarf. Britta was an active member of a Zionist youth group and, when school attendance was also prohibited, worked in the so-called Grabeland, a garden plot in the Jewish section of Vienna’s Central Cemetery, one of the few public spaces still accessible to Jews. They grew vegetables there in the open spaces, which were then delivered to the Jewish Rothschild Hospital. In addition to the hard work, it was also the community of peers that encouraged them.

From 1939 onwards, however, he and his family also attempted to emigrate to England, Australia, or the USA. Unfortunately, all efforts failed.4 Britta Lamberg herself described wearing the Star of David as “odd.” She and her friends often circumvented access restrictions to parks or cinemas by covering the Star of David with a bag or scarf. Britta was an active member of a Zionist youth group and, when school attendance was also prohibited, worked in the so-called Grabeland, a garden plot in the Jewish section of Vienna’s Central Cemetery, one of the few public spaces still accessible to Jews. They grew vegetables there in the open spaces, which were then delivered to the Jewish Rothschild Hospital. In addition to the hard work, it was also the community of peers that encouraged them.

Britta Lamberg held many Zionist meetings in her parents’ apartment. They sang Hebrew songs, dreamed of helping to build Eretz Israel, and always sang Hatikvah at the end of the meeting.

She increasingly noticed that her friends and relatives were becoming fewer and fewer, and that emigration, deportations, and even numerous suicides were visibly diminishing the Jewish community.5 In September 1942, the Lamberg family was also ordered to go to a collection camp in Vienna’s 2nd district, from where they were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp shortly afterwards, on October 9, 1942.6 As the overcrowded passenger train pulled out of Vienna, reality hit Britta. At that moment, she felt uprooted, rejected by her hometown of Vienna, and robbed of her identity as an Austrian.7

She increasingly noticed that her friends and relatives were becoming fewer and fewer, and that emigration, deportations, and even numerous suicides were visibly diminishing the Jewish community.5 In September 1942, the Lamberg family was also ordered to go to a collection camp in Vienna’s 2nd district, from where they were deported to the Theresienstadt concentration camp shortly afterwards, on October 9, 1942.6 As the overcrowded passenger train pulled out of Vienna, reality hit Britta. At that moment, she felt uprooted, rejected by her hometown of Vienna, and robbed of her identity as an Austrian.7

Lucie Fried, Heinz Berger, and Britta Lamberg (1st from right) at the Grabeland

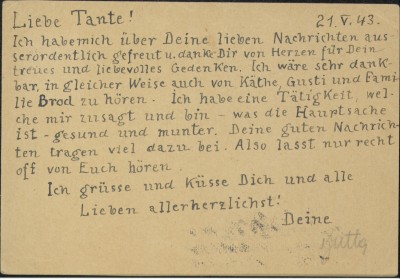

Upon arriving in Theresienstadt, Britta could choose whether she wanted to be housed with her mother or with the other young people. She chose to stay with her comrades, but always felt guilty about her mother.8 Because of their separate accommodations, they stayed in touch with their father via correspondence cards. They also exchanged messages with Louise’s sister, Grete Zeller, who was still in Vienna. Britta also used codes in the cards to her aunt in Vienna; for example, greetings to the Brod family meant that Brot (bread) was urgently needed in Theresienstadt.

Two years later, on October 16, 1944, first Ernst and Louise Lamberg, and then, on October 19, Britta Lamberg were taken to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. This was the final phase of deportations from Theresienstadt to extermination camps. Of the 18,402 people deported between September 28 and October 28, 1944, only 1,574 survived.9 Ernst and Louise Lamberg were presumably murdered in the gas chamber immediately after their arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau.10 As Britta was led to her quarters after the selection at the ramp, she asked one of the Jewish Kapos accompanying her about the chimneys and the smoke. His reply was: “You’ll find out soon enough.” She vividly describes the atmosphere of total threat that surrounded her in Birkenau. On November 3, 1944, Britta was transported from Auschwitz to the Mauthausen concentration camp subcamp in Lenzing, which had been established just a few days earlier, and assigned as an unskilled laborer in the rayon factory five kilometers away. On the same day, she received the armband with the prisoner number 701.11

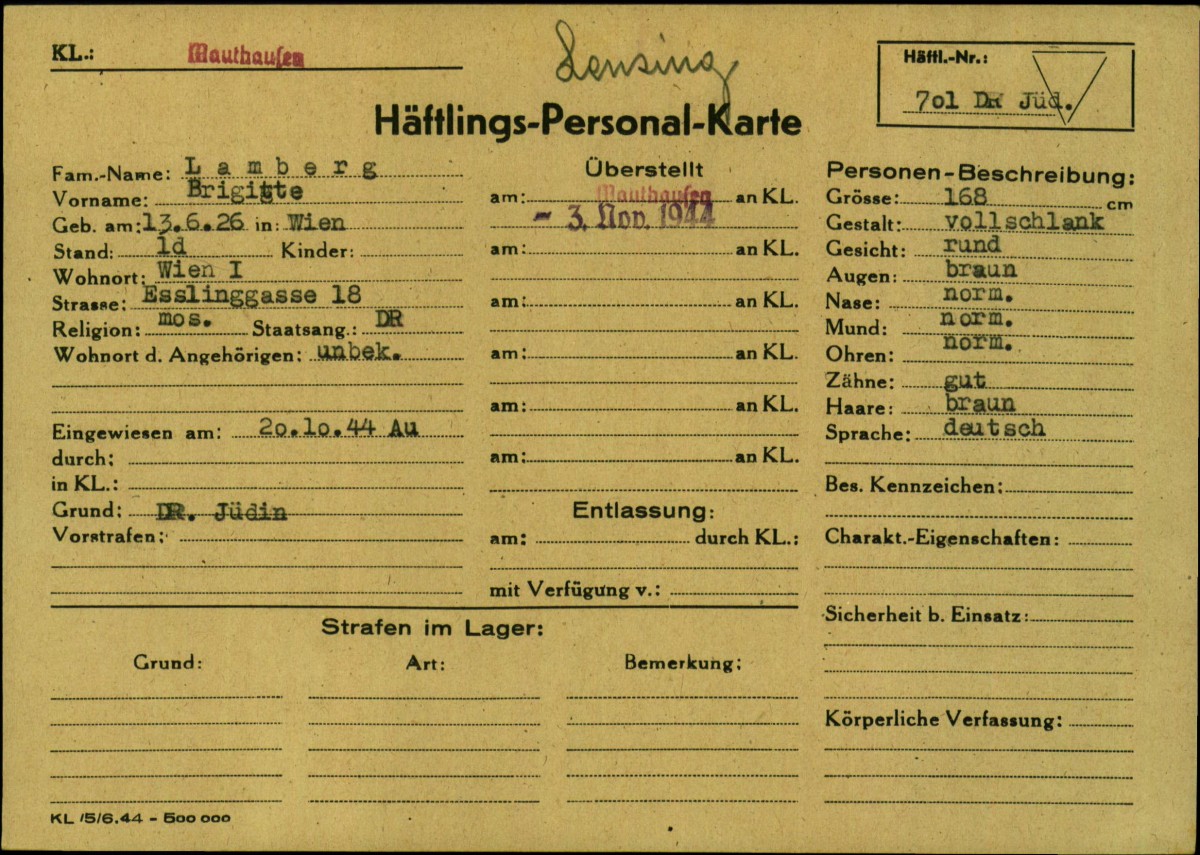

Britta Lamberg’s prisoner registration card, Mauthausen concentration camp/subcamp Lenzing, Arolsen Archives

In 1997, Britta Lamberg donated numerous documents, photographs, and her prisoner armband to the Jewish Museum Vienna. She explained that, due to a lack of ink supplies, she was not tattooed like others in Auschwitz and was given this armband instead.12 However, research revealed that she first received the armband in Mauthausen. In November 1944, numbers between 460 and 970 were assigned to newly arrived women there. The tattooing of prisoners in Auschwitz was probably no longer carried out consistently by the late summer of 1944 due to overcrowding. Only prisoners who were assigned to remain in the camp were tattooed, and not all those who, like Britta, were scheduled for further transport.13

© JWM

After the liberation of the Lenzing camp on May 5, 1945, Britta Lamberg first came back to Vienna. Even then, she intuitively knew that she would never see her parents again. For a long time, however, she dreamed, against her better judgment, that her father might be in Russia and her mother would be waiting for her somewhere else. The return to Vienna was extremely painful for her. She visited her old apartment, where a stranger was now sitting at her father’s desk. The thought of living in Vienna was unbearable for her, so after just a few days, she moved in with relatives in what was then Czechoslovakia. She wouldn’t revisit Vienna until 1983.14

Britta Lamberg and her fellow prisoners in the Lenzing subcamp after the liberation in May 1945

Since the few surviving relatives were in Great Britain, she also emigrated there in 1947. Upon completing her training as a nurse, she worked in obstetrics, among other fields. She spent several years working in various parts of Africa and also lived for a time in New Zealand. Returning later to England, she completed a degree in history and literature in her retirement. Britta Lamberg joined a Reform synagogue and became an active member of the liberal community. She died in London on April 22, 2020.15

[1] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[2] Ernst Lamberg, Louise Lamberg, Victims Search online, Documentation Centre for Austrian Resistance, http://www.doew.at (accessed March 4, 2025).

[3] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, Jewish Museum Vienna, inventory number 25349.

[4] Letter from Britta Lamberg to Reinmar Fürst dated September 8, 1939, undated letter from Britta Lamberg to Reinmar Fürst (before June 1940), Jewish Museum Vienna, STU/II/104, inventory number 5706.

[5] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[6] Transport list dated October 9, 1942, Documentation Centre for Austrian Resistance, http://www.doew.at (accessed March 4, 2025).

[7] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[8] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[9] Theresienstadt, online search, Documentation Centre for Austrian Resistance, http://www.doew.at (accessed March 4, 2025).

[10] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[11] Brigitte Lamberg’s prisoner registration card, Arsolen Archives, https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/document/1874094 (accessed March 4, 2025); KZ Außenlager Lenzing (Lenzing concentration camp subcamp), Mauthausen Guides, https://www.mauthausen-guides.at/aussenlager/kz-aussenlager-lenzing (accessed March 4, 2025).

[12] Conversation with Britta Lamberg, conducted by Christa Prokisch, 1997, written notes, JMW Archive.

[13] Häftlingsnummernverzeichnis, 17 IKRK 80/IST Archive, Arolsen Archives, p. 3, p. 21, https://eguide.arolsen-archives.org/fileadmin/eguide-website/downloads/H%C3%A4ftlingsnummernverzeichnis_dt.pdf (accessed March 4, 2025).

[14] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[15] Obituary for Britta Lamberg, written by Rabbi Alexandra Wright, Hesped, https://hesped.org/person/britta-lamberg/ accessed March 4, 2025).

[2] Ernst Lamberg, Louise Lamberg, Victims Search online, Documentation Centre for Austrian Resistance, http://www.doew.at (accessed March 4, 2025).

[3] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, Jewish Museum Vienna, inventory number 25349.

[4] Letter from Britta Lamberg to Reinmar Fürst dated September 8, 1939, undated letter from Britta Lamberg to Reinmar Fürst (before June 1940), Jewish Museum Vienna, STU/II/104, inventory number 5706.

[5] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[6] Transport list dated October 9, 1942, Documentation Centre for Austrian Resistance, http://www.doew.at (accessed March 4, 2025).

[7] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[8] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[9] Theresienstadt, online search, Documentation Centre for Austrian Resistance, http://www.doew.at (accessed March 4, 2025).

[10] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[11] Brigitte Lamberg’s prisoner registration card, Arsolen Archives, https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/document/1874094 (accessed March 4, 2025); KZ Außenlager Lenzing (Lenzing concentration camp subcamp), Mauthausen Guides, https://www.mauthausen-guides.at/aussenlager/kz-aussenlager-lenzing (accessed March 4, 2025).

[12] Conversation with Britta Lamberg, conducted by Christa Prokisch, 1997, written notes, JMW Archive.

[13] Häftlingsnummernverzeichnis, 17 IKRK 80/IST Archive, Arolsen Archives, p. 3, p. 21, https://eguide.arolsen-archives.org/fileadmin/eguide-website/downloads/H%C3%A4ftlingsnummernverzeichnis_dt.pdf (accessed March 4, 2025).

[14] Interview of Britta Lamberg by Nathalie Lettner, Vienna 1997, inventory number 25349.

[15] Obituary for Britta Lamberg, written by Rabbi Alexandra Wright, Hesped, https://hesped.org/person/britta-lamberg/ accessed March 4, 2025).